In transcribing the Ashburton Hospital Register, 1882 – 1908, several cases of hydatid infections were noted. None was as distressing as the case of little Ethel Broker. She was first admitted to the Ashburton Public Hospital just after her fifth birthday and before she was ten she had been admitted six more times, had two major abdominal operations and spent a total of 296 days in hospital.

Her final recorded admission was in 1907 for 85 days when a hydatid cyst was drained and one would hope she suffered no further hydatid infections.

A century later, in 2002, New Zealand had been officially declared free of hydatids by the Ministry of Primary Industries, fifty-two years after an intensive eradication campaign.

Two other countries, Iceland and Tasmania, had also made a determined effort to eliminate hydatid disease and were provisionally declared free of it in 1977 and 1996, respectively. As hydatids are endemic wherever sheep and dogs live in close proximity, eradication was achieved in these three countries by education, strict feeding regulations for dogs (raw sheepmeat and offal were prohibited), combined with a compulsory six-weekly treatment with the drug arecoline and movement control.

Today, for the vast majority of New Zealanders hydatids is more or less unknown. It is a disease caused by a small tapeworm parasite Echinococcus granulosus, barely visible to the naked eye, that can have devastating consequences for those contracting the disease.

In the 1940s it was estimated that one in seven cases proved fatal. No-one was immune to this disease: neither adult nor child whether male or female, rural or urban all were vulnerable. Ethel Broker was a child living in an urban area.

Dogs and sheep

The hydatid parasite is carried by dogs without any symptoms of infection. Sheep become infected while grazing in areas contaminated with dog faeces. Dogs become infected by eating the meat or organs of infected sheep and in turn humans become infected by ingesting eggs of the parasite, usually through close contact with dogs. Person-to-person or sheep-to-person transmission cannot occur.

In human beings these parasites form slow growing, fluid-filled cysts which necessitate removal. They can become very large or occasionally calcify and never cause any trouble. Most commonly these cysts occur in the liver or lungs but other organs can also be infected and they are usually symptomless until they become quite large or rupture.

Any symptoms are non-specific – stomach upsets, diarrhoea, unexplained weight loss, swollen abdomen, anaemia, weakness and fatigue which can all be associated with many other conditions making it a difficult disease to diagnose.

The disease was recognized by ancient scholars but it was not until the late 19th to early 20th centuries that the connection between dogs, sheep and humans was established.

Treatment

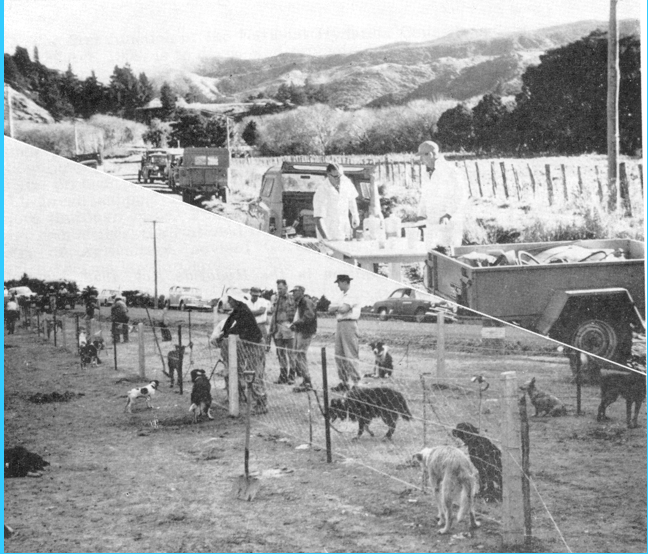

For doctors practicing 60 years ago hydatids was not an uncommon disease ꟷ Dr Patrick Cotter in Christchurch operated on 40 such cases through the 1960s and may have used the scoop-like instruments shown here for removing the more solid parts of cysts, the liquid remainder being removed by suction. It was a delicate operation because any daughter cysts that escaped could cause further infections.

Eradication in New Zealand was a farmer-driven initiative as the sheepmeat industry could no longer ignore the falling export returns for meat sold in Europe as increasing numbers of carcases were rejected because of the growing incidence of hydatid cysts. In addition the extent of human suffering could no longer be ignored. The disease killed more than 140 people between 1946 and 1956.

Many years before, in February 1914, the Ashburton Guardian had reported on a paper, ‘Hydatid Disease’ given by Dr (later Sir) Louis E Barnett of Dunedin at a Medical Congress in Auckland, where he not only detailed the estimated financial loss to the country through the rejection of export meat carcases but also the means by which this loss could be minimised.

Barnett advocated for measures that were ultimately adopted through the latter half of the 20th century, education, and control of dogs (feeding and movement) coupled with compulsory drug treatment.

This was all too late for little Ethel but today the success of the programme followed means that most people under fifty have little knowledge of the disease and the havoc it wrought for many families both rural and urban or the financial loss to New Zealand’s export returns.

Anyone who wants to know more about the eradication of hydatids in New Zealand should read H M Anderson’s thesis ‘Hydatids: a disease of human carelessness in New Zealand’ available through Otago University.

By Margaret Bean.

Captions

- Hydatid scoops used for removing the solid matter from hydatid cysts comes from Pat Cotter’s autobiography Tonsils to Toenails : The Life of Pat Cotter, Christchurch surgeon and tree farmer by Claire Le Couteur, 2016. Courtesy of the Cotter Medical History Trust.

- A typical dog dosing strip. Technicians trained by the National Hydatids Council dosed the dogs in the presence of their owners with the drug, arecoline, and collected the faecal samples for testing for hydatid infection. Courtesy of Ministry of Primary Industries.

- Details of Dr Louis Barnett’s paper were widely reported throughout New Zealand. His name unfortunately was misspelled in the Guardian’s article.

- John Butterick of Wakanui with his very healthy dog Flora McDonald.

Leave a comment